please keep art safe

On the October 3, 1992 live broadcast of Saturday Night Live, Irish singer-songwriter Sinéad O’Connor was the evening’s musical guest. She performed an a capella version of Bob Marley’s War, changing the lyric of “racism” to “child abuse.” And while singing the final lyric “evil,” O’Connor held up a photograph of Pope John Paul II, tore it to bits, and declared to the audience, “fight the real enemy.” Silence followed. Cut to commercial.

The producers of SNL were caught off guard and received over 3000 calls of protest. O’Connor defended her actions calling to task the Catholic Church for allowing the abuse of children by clergy to go unchecked (strangely prescient considering recent revelations of abuse in the church). Over the ensuing weeks O’Connor was generally vilified – three weeks later at a Bob Dylan tribute concert in Madison Square Garden, she was booed off the stage.

To Catholics and many others, Sinéad O’Connor’s defiling of a photo of the Pope was an act of blasphemy. And it may sound surprising, but if not for a landmark Supreme Court decision in 1940, O’Connor could have been arrested and prosecuted for inciting breach of the peace and criminal blasphemy.

Back in 1939, Newton Cantwell, a Jehovah’s Witness, along with his two sons were proselytizing in a Catholic neighborhood in Connecticut. Carrying a portable phonograph and literature, the three went knocking door to door. They played for two gentleman a record that described all organized religious systems as “instruments of Satan,” and called out the Roman Catholic Church in particular. Deeply offended, the men basically wanted to throttle the Jehovah’s Witnesses, but instead called the police. They were arrested and convicted for inciting breach of the peace among other charges.

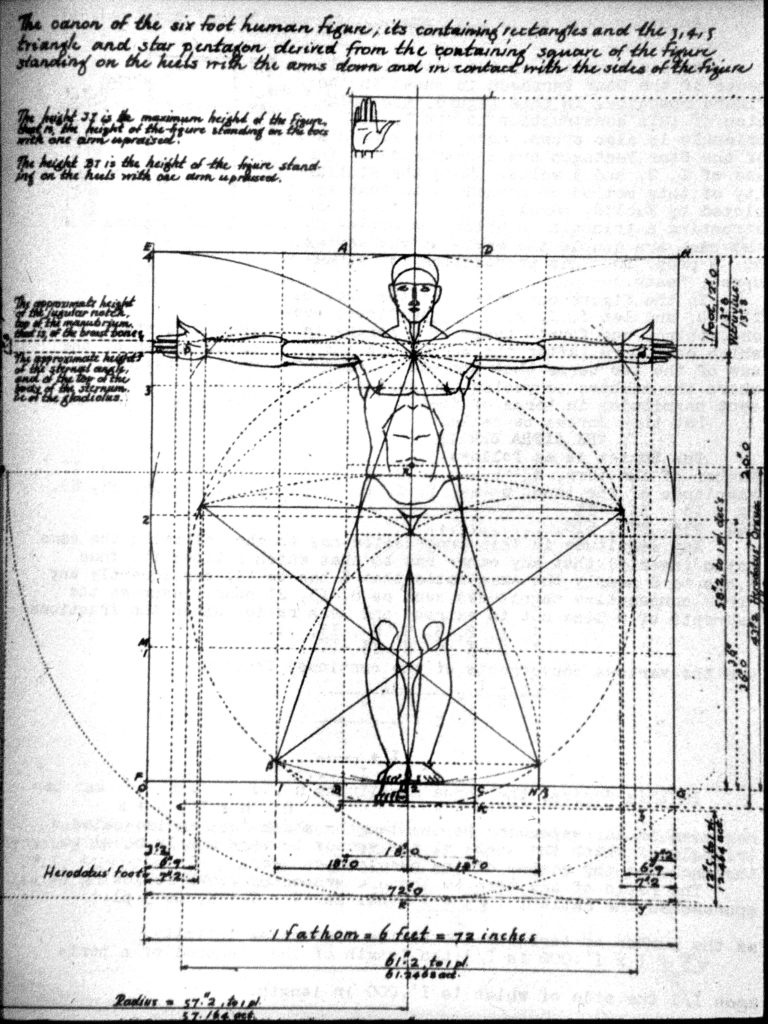

The Cantwells appealed and claimed that they were denied their freedom of speech and prohibited their free exercise of religion under the first Amendment. The 1940 Supreme Court agreed unanimously and set a precedent that basically made any previous laws against blasphemy in the US a dead letter. The 1940 decision explains, that “the tenets of one man may seem the rankest error to his neighbor.” And that in a democracy an individual’s right to resort to exaggeration and vilification are liberties “essential to enlightened opinion.” And under the “shield” of these liberties, “many types of life, character, opinion, and belief can develop unmolested and unobstructed.”

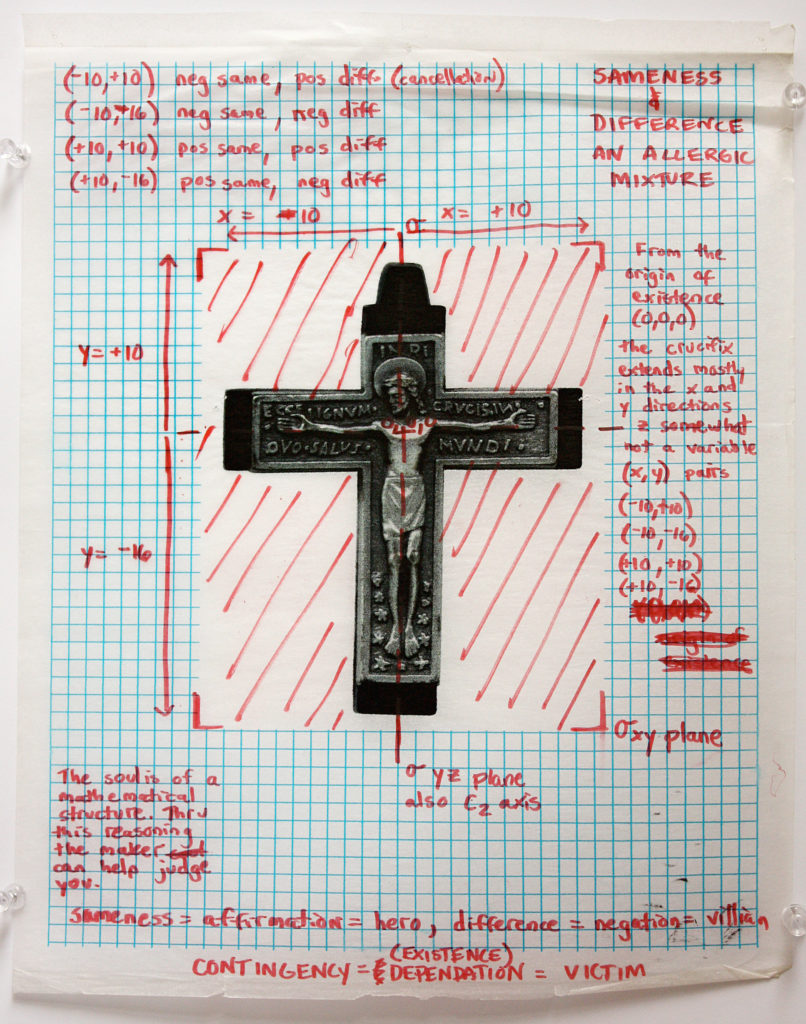

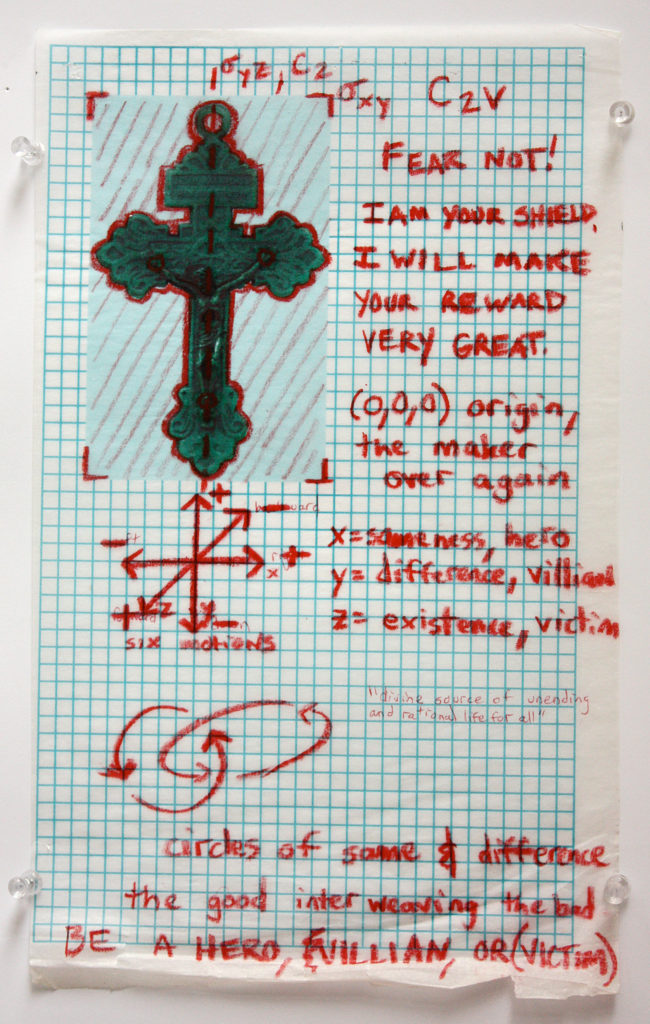

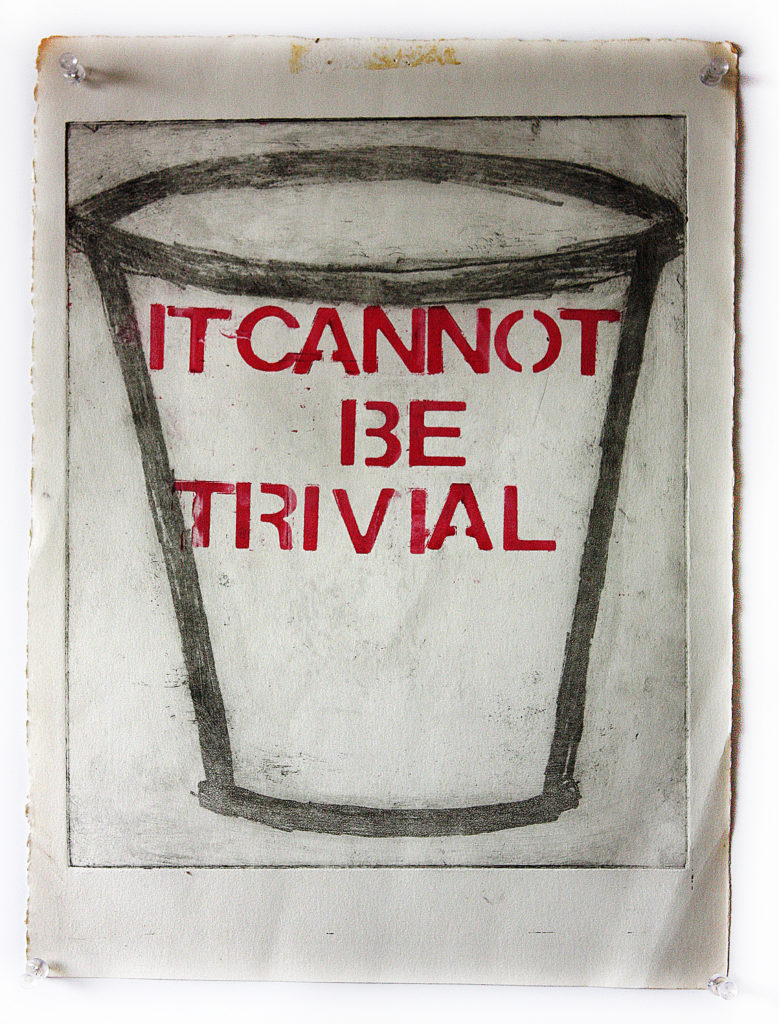

That an individual has the right to offend someone, and even to do so deeply, to make their point – in speech, writing, art, performance, film, etc. – is a tremendous right. It protects from criminal prosecution, but it does not protect from outrage, rejection, and recrimination. The “Culture Wars” and “Political Correctness” of the nineties showcased how to better control unsafe expression. There was the gutting of the NEA’s budget and the addition of “advisory language” regarding decency in grant applications. Both in reaction to funding a retrospective of the sexual explicit photographer Robert Mapplethorpe and the photograph by Andres Serrano of a crucifix immersed in his own urine. Or there was the prosecution of University of Pennsylvania student Eden Jacobowitz under the school’s speech code. He was accused of intending “water buffalo” to be a racial epithet yelled at some late night noisemakers who happened to be black.

A return to the days of prosecuting for blasphemous statements may not be possible. (In 1811 People v. Ruggles, the conviction of a New Yorker was upheld for saying “Jesus Christ was a bastard and his mother must be a whore.” NY Supreme Court Justice Hale affirmed that the danger of of blasphemy lay in its tendency to “strike at the root of moral obligation” and called blasphemous “words and actions dangerous to the public welfare.”) So the preference became to find ways to encourage self-censorship. If unsure whether a particular piece of speech may be offensive to some or most individuals, it’s better left unsaid.