cross symmetry

My mother would implore me to hold the cross higher, “You’re so tall, you can hold the cross higher than anyone else. Use your height.”

I was an acolyte for an Episcopalian church for a number of years. I started as a torch bearer for the youth procession after Sunday school. Three of us would run after class to the back of the church, put on our frocks and blouses, and lead the other kids into church with a cross and two torches. I eventually became the cross bearer for the main procession at the start of the service, leading in the way for the pastor and clergy. The height to which I lifted the cross was a point of pride for my mother.

As an acolyte, you never actually sat with your family. The six of us, cross and torch bearers for the service and for the youth procession, sat in the front pew alone. We often got into trouble for not being the model Episcopalian youth we were supposed to be. We would stand, kneel, and sit when asked, but we rarely read from the prayer book or sang from the hymnal when we should have. We’d open to the pages we were supposed to, but only to check them off a list of the various portions of the service. I would actually use my fingernail and “strikeout” each part of the mass listed on the weekly program.

I also spent grades 1-5 in a Catholic school and four years as an undergraduate at a Catholic college. I didn’t intend to surround myself with so much formal religious culture given that I’ve never felt comfortable with all the rituals and symbols, and was never a deep believer in what they were to represent. That there was a system of belief certain of “the way,” just seemed silly. How could you know for sure?

Maybe it was the science side of my brain, which would question, “show me the proof!” And I wasn’t looking for someone to prove to me that God exists, but that these religious words, symbols, and actions were the answer, the only answer.

In an earlier post, I mentioned that I spent a year in a chemistry Ph.D. program at the University of Chicago. By the end of the year I knew I would leave for art school and would not join a research group. But I was still required to take a research course to finish my Master’s degree. The chair of the department suggested a mini research project that he felt would be appropriate given my change in academic pursuits. The final project was titled Quasicrystals, Ancient Building Science, and the Golden Mean. It was followed by a quote from the mathematician Roger Penrose:

It is a mysterious thing in fact how something which looks attractive may have a better chance of being true than something which looks ugly.

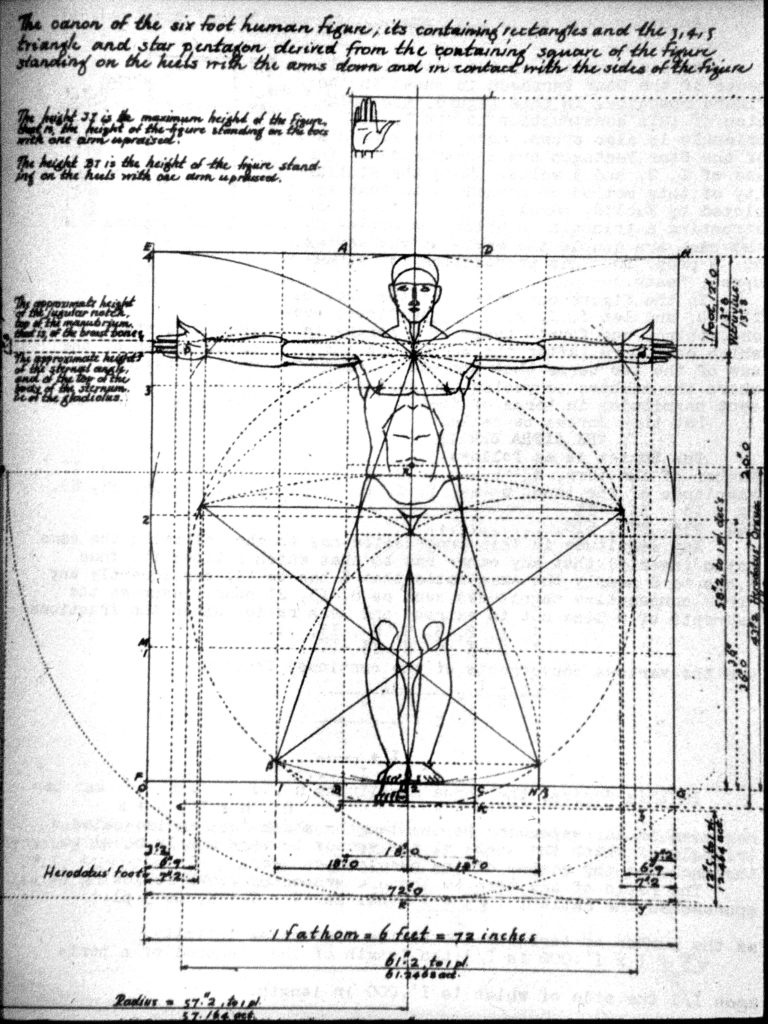

Penrose was speaking about the researcher’s desire for the more aesthetically pleasing solution to be the right solution. This was how I introduced the presentation’s survey of examples in art, science, and religion where symmetry is used to find “perfect” answers. In the process I was introduced to molecular symmetry based in group theory that is a system used to classify molecules by their symmetry. Molecules fall into different symmetrical groups and each group reveals various fundamental properties.

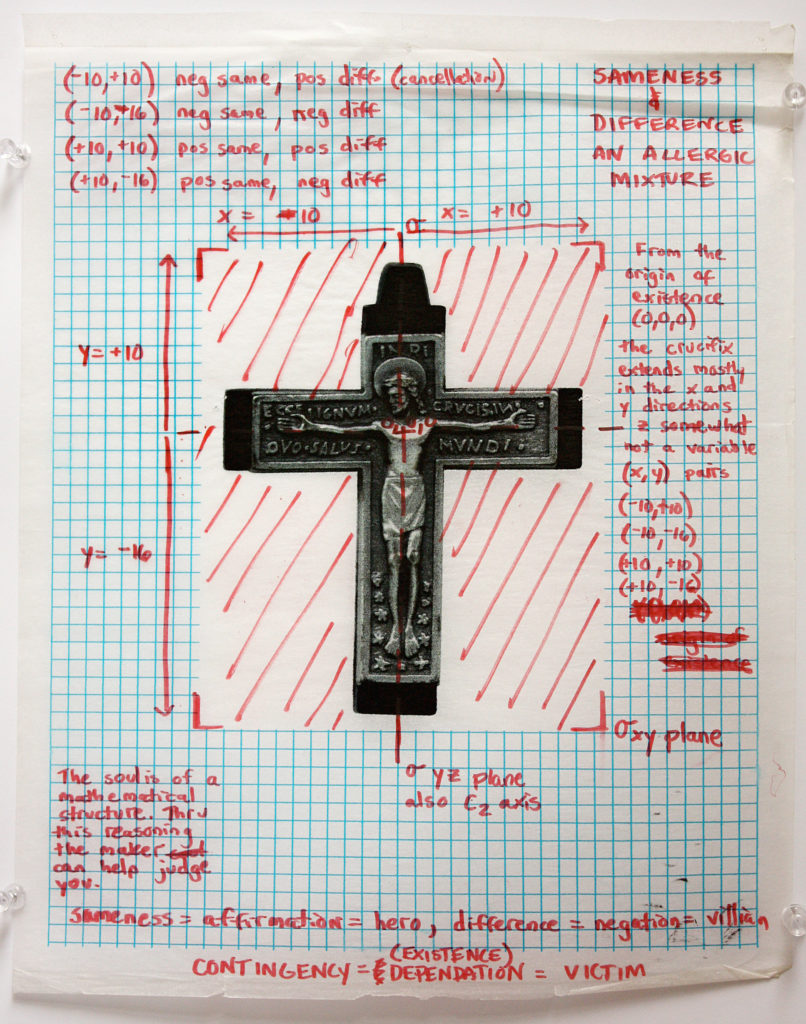

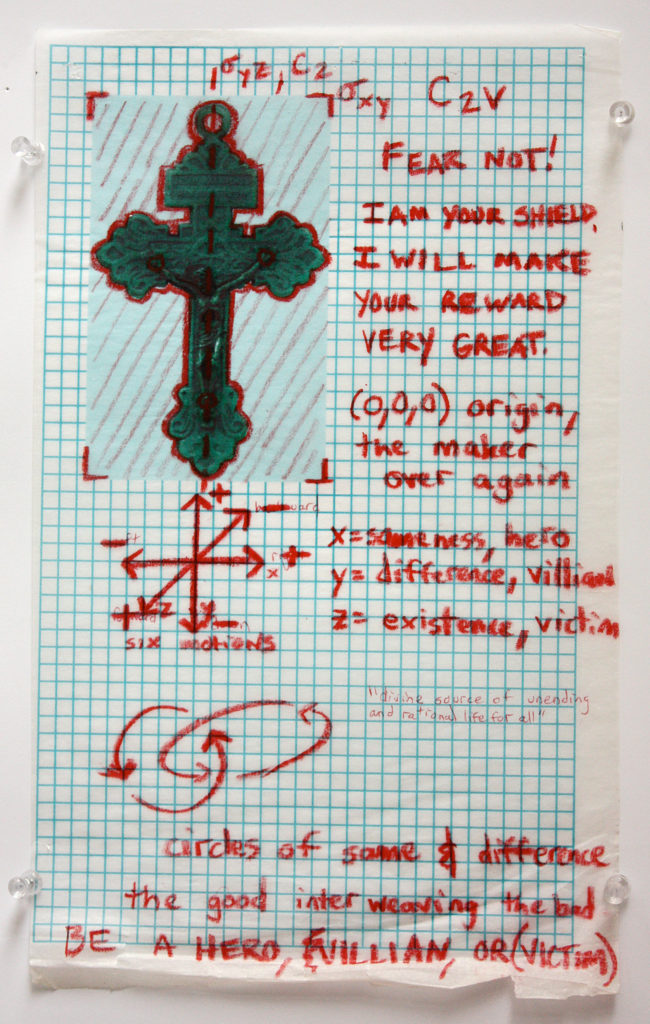

Cross Symmetry analyzes the symmetry of different crosses, as an ancient architect would use the “perfect human form” as a guide to build the Parthenon.

This new cross symmetry system became a way to affirm, deny, or qualify the value of each crucifix.