transport

I feel lucky that in the four summers I was a lifeguard I only had to make one save. And it was an easy save. While guarding the pool known as the “middle pool” – primarily for 4-6 year olds and running only two to three feet deep – a girl was bouncing along toward the deeper end and lost her footing. A brief slip and her head was under and she did not know how get her feet back under her. And seeing the terrified look in her eyes I knew she needed help. It was simple, I reached in, scooped her up and passed her to her mom who was close by reading a magazine. It was a save though. And I didn’t need to use any of the complex maneuvers learned in lifeguard training. Just a watchful eye and long arms.

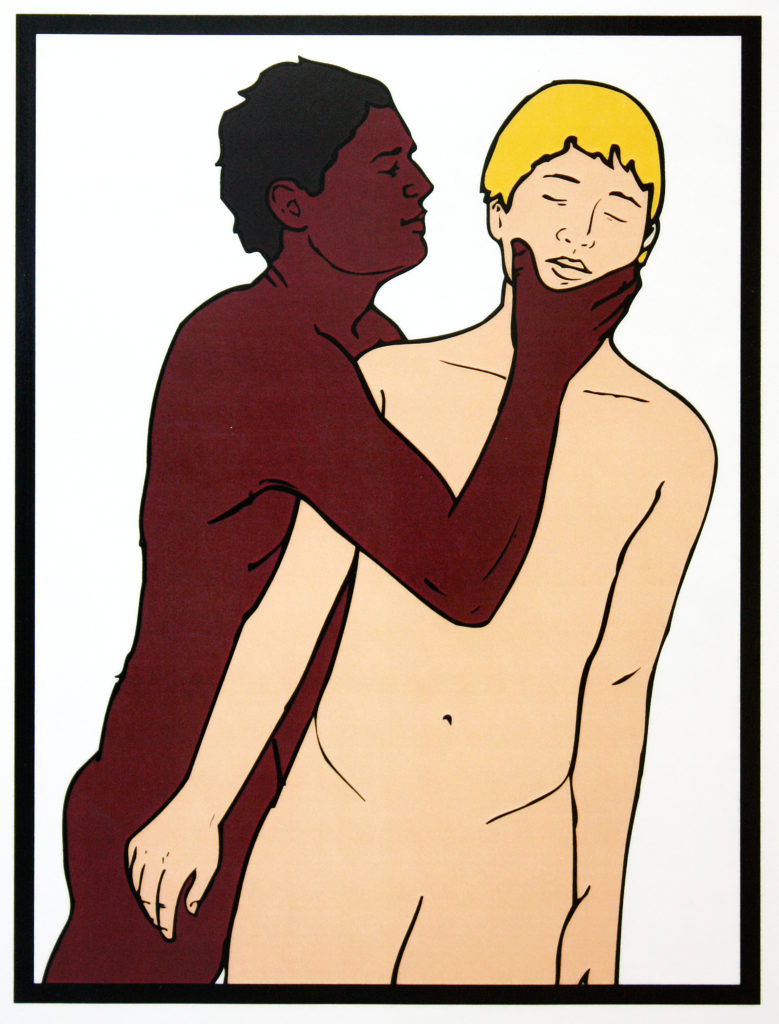

There are a number of moves that you had to practice to rescue a drowning victim – how to support them, transport them, and even defend yourself. Developing the ability to move yourself and the victim through the water fluidly and safely was what you were trained to do. This was of particular importance for a potential victim of a spinal cord injury, someone who was unconscious floating face down in the water. To minimize the amount of neck movement, you were to enter the water without disturbing it. Approach the victim carefully. Cradle the victim’s neck with your hands front and back and your arms bracing the chest and spine. And finally with a swift kick while maintaining this cradle, you would propel yourself underwater while gently rotating the victim face-up so that they might breathe again.

Practicing this maneuver in the lifeguard training class required that we take turns and act as victims. It was always fun to act as the flailing victim who is so freaked-out you end up attacking your rescuer. Your partner would have to push you away, swim underneath you, and come at you from behind to start over. Between this and the spinal victim exercise, you made a lot of physical contact with your partner. And between a bunch of sixteen year old boys and girls there were a number of sexual undertones that went with these exercises.

These were the kinds of things that you knew everyone in the class was thinking about but no one wanted to talk about. “Yes I know that I’m putting my forearm between your breasts while gently placing my hand on your chin. I’m fully engrossed in pretending your back may be broken. That’s all that I’m thinking about, really.” You were supposed to be asexual and everyone else was asexual.

I imagined that in an actual emergency situation hopefully my training would take over. All the physicality would be a means to saving a person from drowning. And all the nuances of body language would disappear behind the shear terror of being responsible for saving someone’s life.